Ghost Towns and Abandoned Attractions of Indiana: Pt. 2

May 21, 2021

In our last part of the Abandoned Ghost Towns and Attractions in Indiana, we took a look at a couple of ghost towns that can still be visited today, and the history behind them. This second part will be a little different, however, since these locations are not necessarily towns. Rather, they are former attractions that time left behind.

Jungle Park Speedway

As you trek through Turkey Run State Park in Parke County Indiana, you may be confused by a sudden man-made structure coming into view. As you approach, you’ll notice it’s a wooden grandstand with the words “Jungle Park” painted on the back in black paint. While the name itself doesn’t give away its purpose, the open field it faces will.

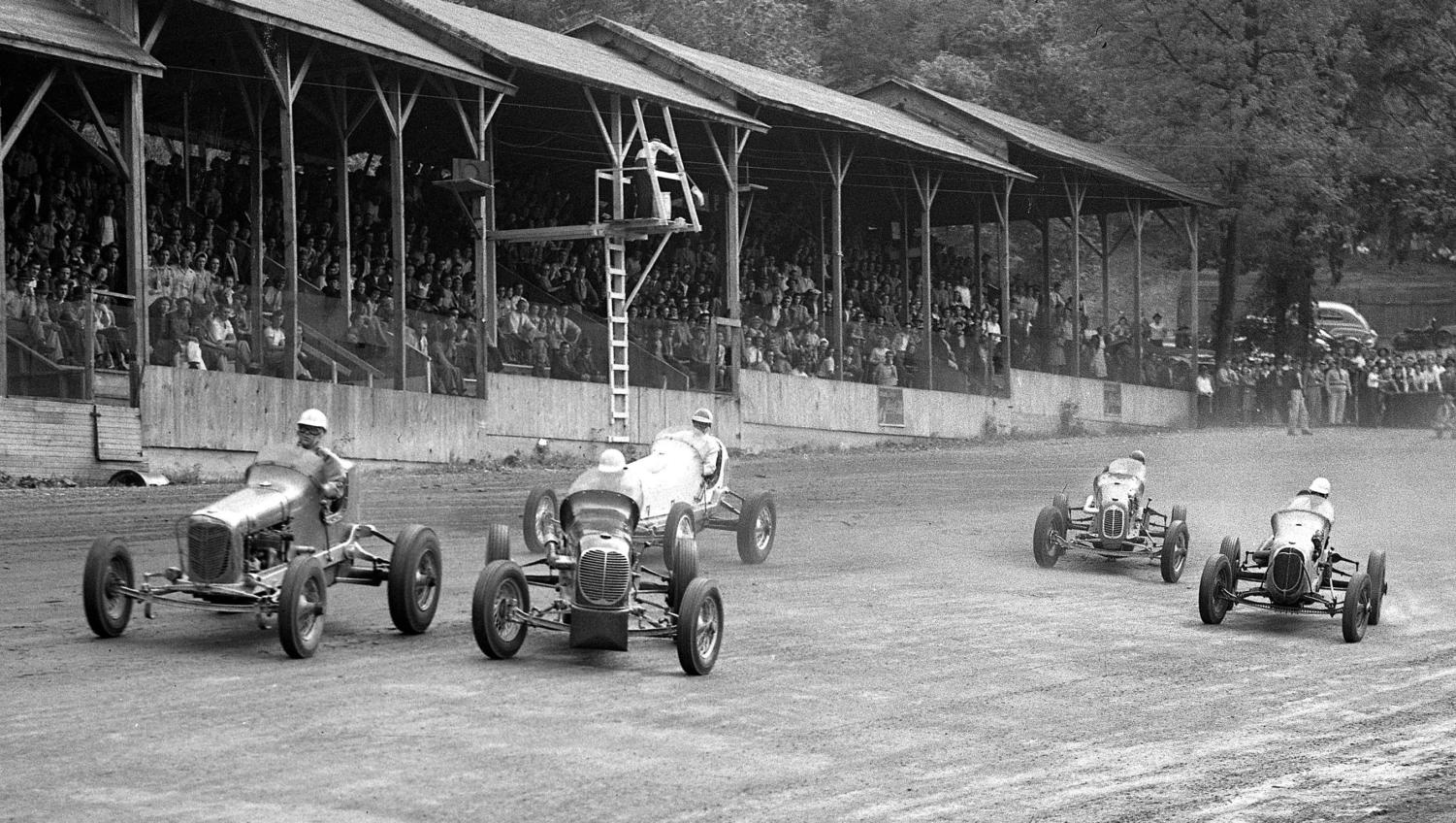

Jungle Park was a quarter-mile-long racetrack built in 1926, and, from the get-go, it drew big names and big crowds. In those days, drivers who competed in the AAA Championship Trail (now known as IndyCar) didn’t make money as drivers do now. In addition, the championship often had long gaps between races, so drivers needed a way to make ends meet in between the big events.

The answer? To race at local tracks.

Jungle Park was one of those local tracks. Eight drivers who regularly competed at Jungle Park went on to win the Indy 500. Drivers like Wilbur Shaw used it as a way to test their cars in competition, before taking them onto the Championship Trail.

The track was also known for being incredibly cheap. In those days, safety was not a concern, and deaths were common in the motorsport world. Racecar drivers were the men who stared death in the face for the amusement of their fans week in and week out, and, sometimes, they blinked.

Jungle Park had no walls around its banked turns. You either hit a tree in the woods that surrounded the track, or you traveled down in the embankment into Sugar Creek. One former driver even stated that the track lacked a stopwatch. During qualifying for races, the flagger simply held a silver dollar in his hand and acted as if he was timing the cars. How they decided who started where is anyone’s guess.

With the lack of safety features, many people lost their lives at Jungle Park. One man flew off the track and went headfirst into a tree, damaging his skull and dying on impact. In another instance, a car flipped and caught fire. Spectators, not being held back by any sort of wall, descended upon the car and began pouring beer on it to attempt to put out the fire. The “safety crews” lacked any real equipment to deal with fires, so if your car caught fire, you could either climb out or burn to death.

Jungle Park’s attendance slowly began to decline in the 1950s, and by 1955, the place had closed down. However, for one last hoorah in 1960, the track reopened for one more race: a midget car race that would end in disaster.

During the race, Arlis Marcum hit a pothole in the track and was launched over the embankment into a crowd of fans. Annabelle Sigafoose was watching the race while sitting on a blanket. She attempted to avoid Marcum’s car as it flew towards her, but the car was much faster. It struck her head-on and dragged her down the embankment. She was killed almost instantly.

Jungle Park shut its doors after that incident, never to reopen them again. The track still stands in the woods, silent. A complete about-face from the days when the engines roared, and fans cheered. It’s almost peaceful.

The grandstand is old and rickety, looking like it could collapse at the slightest provocation. The four other grandstands that once stood have now collapsed and have been removed from the site. The Jungle Park Pitstop restaurant with a windmill still stands nearby in fairly good condition—for being well over 60 years old and dilapidated.

The racing surface is now completely covered by grass and soil. An old midget racer stands rotting away nearby, but how it got there is unknown. The owners of the property used to sell canoes there for the nearby Sugar Creek, but even the canoes are gone. The property now simply stands as a remnant of a bygone time of racing.

Rose Island Amusement Park

The amusement parks of today, while rooted in the origins of the parks of the 20s and 30s, are vastly different than those from an earlier time. Nowadays, parks are full of rides, roller coasters, shows, huge water parks, food stands, and many shops. Back at the start of the 20th century, however, amusement parks were simpler.

Rose Island began its life as Fern Grove in the 1880s as a recreational area for church camps and church family outings. The name originated from the large amount of ferns that grew in the area. The space provided ample green space for picnics and games for children. In 1881, the Louisville and Jeffersonville Ferry Company purchased the property as a stop along their routes. This increased revenue for Fern Grove and the area began to expand to include a restaurant.

An ad in the IndyStar from 1917 described the land as having “Comfortable, commodious cottages, completely furnished [that]will easily accommodate for four to eight persons. Excellent food and splendid restaurant service- all combine to make Rose Island a delightful place at which to spend a day, week, or an entire season.”

In 1923, David Rose bought the property and decided to expand it into the then young world of amusement parks. Spending $250,000 (3 million today), he built a brand new roller coaster (called a Racing Derby by the park) named the Devil’s Backbone, a new hotel, a swimming pool, a Ferris wheel, and a zoo.

The petting zoo contained wolves, monkeys, turkeys, other farm animals, and a black bear named Teddy Roosevelt. A skating rink and dance hall were also constructed.

However, when the Great Depression hit in 1929, attendance began to wane. The park still operated but was in danger of closing every season. When the Ohio River Flood of 1937 damaged the park, the damage was unrepairable with the money the park had left. Rose decided to close it and leave what remained to be reclaimed by nature. The footbridge used to cross over onto the island collapsed, leaving no way for curious explorers to get onto the property. The park fell into a state of disrepair and isolation.

Charlestown State Park was given the land in the mid-80s, allowing for the general public to access the island once again if they owned a boat that could reach it, as the bridge no longer existed. The first visitors to the island in over 45 years discovered that the park had been essentially reclaimed by nature. Most of the former buildings were gone, save for a few piles of bricks

The swimming pool was still in good condition, filled with green water, indicating that nobody bothered to drain it. The fountain still stood, and the entry gates also remained in a damaged fashion.

Today, access to the old park is much easier. The footbridge has been rebuilt, and if you take Trail 3 in Charlestown State Park, it will lead you right over the bridge and onto the island. The park has taken the liberty of adding a display that goes into the history of the site and marks areas where attractions once stood.

It’s always fascinating to think about what the park may have been like if it had survived the Depression. Would it have morphed into an amusement park like King’s Island or Cedar Point? Would it have inevitably closed down the road due to lack of attendance? You can speculate all you want as you roam through the once fun-filled paths of Rose Island, but you will never truly know the answer.

As more and more abandoned attractions are being torn down to make way for progress, we are slowly losing bits and pieces of our history. Nature is also speeding up that process. It’s sites like these that we should cherish as relics of the past.